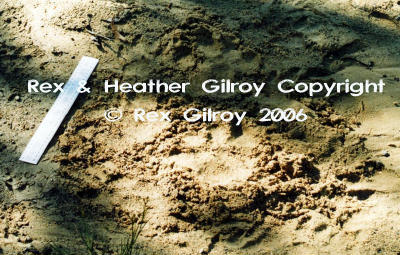

Marsupial Tracks © Rex Gilroy 2006Rex Gilroy made a chance discovery of ‘lion’ tracks one morning while on a hike out on Narrow Neck Plateau, when he proceeded to walk up the closed section of fire trail. The paw prints had been made the night before. Rex attempted to follow the tracks up the fire tail and into the bush, but they faded away in the forest leafmould. Later that day, together with Heather, he returned to the site where they prepared a large plaster cast of one section of the tracks.

Read Excerpts From

Out Of The Dreamtime -

The Search for Australasia’s Unknown Animals

by Rex & Heather Gilroy

Copyright

© Rex Gilroy 2006

No part of this publication including all photographs and illustrations may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review, written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast.

Dedication

This book is affectionately dedicated to my loyal, supportive and dedicated wife, and Number One researcher and fieldworker, Heather. This book is also affectionately dedicated to my late father W.F. [Bill] Gilroy [1904-1996], whose tales of his native Scotland and the Loch Ness Monster, led me, from about the age of five [!] to my lifelong research of the natural sciences and the fields of Cryptozoology and relict hominology, which has resulted in this book.

PART THREE

LIONS AND TIGERS OF THE AUSTRALIAN BUSHLAND

__________CHAPTER EIGHT

Australia’s Mysterious Marsupial Lions

Meat-Eaters of the Miocene

Situated some 200 kilometres north-west of Mt Isa, in Queensland’s rugged, dry north-west, is Riversleigh, a remote cattle station, which has since the 1980’s been the focus of much scientific investigation by palaeontologists.

For, encased in the vast limestone deposits that cover this locality, are the remains of untold thousands of animal species, many hitherto unknown to science, dating back 25 million years to the Oligocene period. Carnivorous kangaroos, diprotodonts, 7-metre length pythons, early ancestors of the supposed now ‘extinct’ Thylacine, primitive platypuses and koalas, giant monitor lizard remains, giant birds, and at least three species of Marsupial Lion.

The best known of these ‘lions’ is Thylacoleo carnifex, and while these marsupial carnivores are best known from the Pleistocene period of the last 2 million years, their fossil history can be traced back to the late Oligocene around 23 million years ago, where the earliest-known species, the cat-sized Priscileo pitikantensis is found. The dog-sized species known as Wakaleo appears in early Miocene deposits around 20 million years ago, to be followed by Wakaleo oldfieldi about the middle Miocene.

Other ‘lion’ species identified from the Riversleigh limestone deposits have been Wakaleo vanderleuri [middle Miocene 21.6 million years ago], and late Miocene Wakaleo alcootaensis [about 10 million years ago], small dog-sized Thylacoleo hilli [late Miocene], and leopard-sized Thylacoleo crassidentatus of the Pliocene period [around 5 million years ago onwards].

During 1989 remains of yet another ‘lion’ were found. It was a ‘lion’ with a difference, for it was a “missing link” between the two great lineages of marsupial lions, the Wakaleo and the Thylacoleo branches of the family tree. As early as 1961 remains of the oldest species known, came from the late Oligocene deposits of the Tanami Desert of South Australia. This species, Priscileo pitikantensis roamed Australia around 25 million years ago.

In 1989 the Riversleigh limestone released remains of yet another ‘lion’, the perfect skull of an incredibly tiny, very primitive species no larger than a house cat closely related to P. pitikantensis.

In February 1972, in the course of a fossil search in the Megalong Valley, below Blackheath in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, the author was exploring a deep cleft in the cliffs which led down into a secluded grotto through which a small creek trickled over quartz, sandstone and ironstone pebbles.

It was here that I spotted a large lump of curiously shaped red ironstone to one side of the creek, which seemed to stand out from all the other rocks. Picking it up and turning it about in my hands, I was surprised to find it was a mineralised skull complete with the lower jaw fused to the palate, and although crushed slightly flattish by past ages of geological pressure during the mineralisation process, I could see it was the skull of some long-vanished marsupial species, probably late Pliocene and early Pleistocene in age, which could make it anywhere between 2 to 5 million years old.

The fossil had been crushed on its right side against a hard surface, yet this has not been sufficient to distort vital features of the skull’s original shape. Its cranium was flattish with a forehead that sloped up from two clearly visible eye sockets and a short muzzle. Two broken mineralised incisor teeth project outwards from the fused lower jaw. This heavy little fossil measures 15.5cm from muzzle to back of skull by 12.2cm in depth and 7.5cm width across the dome.

Comparison with skull-types of the marsupial lions leaves little doubt that this is what the creature was. Which species exactly at present remains unestablished, but the fossil comes from a valley already famous among generations of local farmers for sightings and close encounters with animals of marsupial lion appearance.

Old tales from the pioneer days of the 19th century, of dead calves, lambs or goats, found wedged high up in the forks of trees, where they had been placed by some large tree-climbing marsupial carnivore, or dead cows found near the bases of tall trees, from which their killer had leapt upon them, are rivalled by claims that more than one farmer in the old days, had been knocked to the ground by a large, ‘lion’ or ‘big-cat’-like beast that sprang upon them as they passed beneath overhanging tree limbs upon which one of these creatures had been perched.

The eerie Megalong Valley figures many times in this book, for more than a few mystery creatures are said to inhabit its rugged bushland, and with the possible exception of the notorious black-furred ‘panther’ and Thylacine, has it seems, always been home to the ‘lion’. These animals are by no means confined to the Megalong Valley. This valley backs onto the Burragorang Valley and Jenolan Ranges and the Kanangra Boyd National Park, all of which provide a vast expanse of virtually impenetrable scrub and forestland, in which any ‘unknown’ creatures could survive, hidden from modern human interference.

Northwards from the towns of Katoomba and Blackheath, beyond the Grose Valley, lies the Wollemi National Park, which adjoins the Wollongambie National Park, covering a vast region of some thousands of square kilometres of impenetrable terrain, and it is from around the outskirts of all these Blue Mountains wilderness areas that modern-day reports of the ‘lion’ in particular emanate.

We shall return to the Blue Mountains in due course, but first let us turn briefly to the central western region of NSW, which begins just beyond the Blue Mountains, and which also possesses a long history of ‘lion’ activity.

In fact, it was from the central western town of Wellington that the very first fossil evidence of the Marsupial Lion, Thylacoleo carnifex, came to light in the 1830’s.This evidence consisted of a long ridge-like tooth found in cave dirt at Wellington Caves. When the tooth was sent to England’s most celebrated palaeontologist of that time, Richard Owen, he was utterly confounded. Later discoveries of skull fragments suggested to some that the mystery creature to whom the tooth had belonged had an affinity with the possums, but the unique features of this animal were most definitely very un-possum like.

Of the three pairs of upper incisors of the skull, the first was very large, while the two lower incisors were forwardly inclined. These, together with the enlarged upper incisors, formed a very powerful set of pincers. The remainder of the teeth were small, except for the enormous 4-5cm length carnassial, or cutting premolar tooth present in each jaw. Owen finally named the creature Thylacoleo carnifex [“flesh-eating marsupial lion”] and described it as “one of the fellest of predatory beasts”.

There can be no doubt that Thylacoleo and his relatives were predatory killing machines. During the 1950’s the first postcranial skeleton material was excavated in South Australia and later, further remains were unearthed at NSW sites, which showed scientists that the vertebral column was strong while flexible, and that the limbs were long and very powerful.

All the digits were clawed but the ‘thumb’ supported a huge compressed claw 3-4cm in length. The forelimb could be seen as an efficient striking and holding weapon, while the hind limb was possum like in structure with an opposable first toe, which served to provide a grip and balance in arboreal situations.

Besides the ability to climb trees, Thylacoleo carnifex was well adapted for medium-paced running, particularly when pursuing its prey. It would have leaped upon kangaroos or any other large marsupial, tearing it with its large incisor teeth, which were capable of dismembering any carcass into bite-size bits.

In 1979 a Wellington farmer is said to have observed a large “gingery fur-coloured big-toothed cat-like beast” in the act of tearing away at the flesh of a young cow it had just killed; while at Orange another property owner caused a stir among his neighbours in 1969, when he announced that a dark brown-furred, lion-like animal”, of about 5ft [about 1.5m] length from head to tail, had leapt from a tall gum tree limb early one morning in scrub opposite his house, to bound across the road in front of his gate as he was driving his truck out onto the roadway.

Main Book Index | Mysterious Australia Homepage | URU Homepage | Australian Yowie Research Centre